After claiming that most programmers just can’t

program, and actually

addressing most of the problems to the lack of passion of people who decide to

start a career as a programmer, I would also like to express my point of view

on a tightly related subject: what can be done to improve the situation?

The problem that I was trying to bring up in the spotlights, is that a lot of

people just start (or wish to start) a career in the IT for no particular

reasons. Those are the ones who don’t love and don’t loathe programming, and

they just see it as something that pays their bills. Well, maybe the first

question that I should address, actually is: why is this bad? Sure there

are so many jobs which don’t require passion at all, and people just do them

because a job is just a job, and don’t really care. In my opinion, being a

programmer is different.

There are many people, especially the ones who sit high in the hierarchy of a

company, who see programmers as the last and least important step of a ladder.

They often think that programming is quite of an automated and repetitive task,

and it could basically be done by anyone, with just a little training.

Unsurprisingly, this seems to be the opinion of most common people, who

ignore what programming really is. I wouldn’t want to discriminate among

different types of programming, or different programming languages, but it’s

obvious to me that programming, to some extent, actually can become an

automated an repetitive task. That’s quite the minority of cases, though, so I

will simply ignore them, and focus on the rest.

As anybody who’s a programmer knows, programming is a highly creative task,

that requires good imagination and great problem solving skills. Everybody else

might just see it as “typing stuff on a computer”, and believe me, there’s a

whole lot of educated people who think that programming is a monkey matter.

Hence the term “code monkey”. This term has historically been abused a lot,

by even programmers themselves. A “code monkey” is said to perform a

programming task so easy that even a monkey could do, as the image suggests.

There are two truths about this phenomenon: first of all, luckily, programming

requires far more skills than it’s usually believed; secondly, and sadly, the

majority of people just ignore it.

The problem with lousy programmer is kind of similar to a medal: it’s double

faced. You could actually call it a dog trying to bite its own tail: as

programming is believed to be an easier and easier task, more programmers are

needed; as more and more programmers are needed, more people will jump on the

field; as more and more people try to become programmers, the lousier the

average quality of programmers gets. Unfortunately, what average

non-programming people miss to understand is that although it doesn’t really

take a hard training to become a lousy programmer, it takes a damn hard one

to excel in the art of programming. Moreover, most people just lack the

innate logic mechanisms that make you a potential programmers. Such

mechanisms are developed in your mind when you’re very young, and it’s quite

rare to develop them after your twenty-somethings. With this, though, I’m not

denying that there are a lot of people who actually do develop those mechanisms

in advanced age. I’m just trying to think of the big numbers, here.

So, getting to the point, what went wrong and how can it be fixed? I don’t

think it would be wise to say that what’s wrong is that there’s too much need

of programmers, ergo the average quality was inevitably doomed to lower and

lower over the time. I rather think that the problem is with education. Of

course I can’t speak for all the universities and colleges in the world, but I

can at least try and speak for the one I’ve known personally, or through people

who have studied there. It seems that, as more and more people apply to

Computer Science or related departments, the easier it gets to get in (sorry

for the pun), and to get through with it, i.e. to graduate.

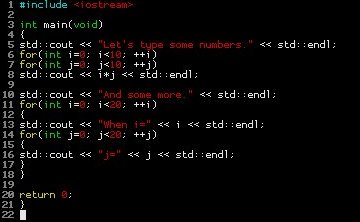

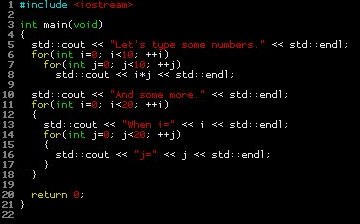

I know this happens most likely in any other faculties, but seeing that there

are people who have been studying CS for three or more years, and still can’t

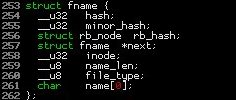

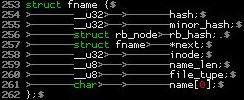

get through the most simple concepts, just doesn’t seem right to me. Yesterday

night, I was sitting in an IRC channel about the C programming language, when

somebody joined in and asked:

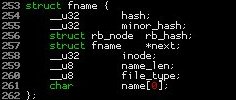

“I just started studying structures in C, and I don’t get them. Can anyone

explain to me what’s the use for them?”

Ok, I don’t really think there’s anything wrong in not getting the point of C

structures right away, but after a little chatting, it turned out that the guy

was in his second year of Computer Science, and this was the second time he

took the C class. Still that wouldn’t be a reason of hatred, of course (not

that I have any hatred), but after another small while it turned out that the

guy didn’t like programming at all, but he just got himself into it because he

applied to CS since he liked to “fiddle around with computers”.

What’s really needed, in my opinion, is a harder and less tolerant educational

system, that would be more selective, rather than pushing everyone forward.

People that find out to be really not made for it, should just give up and move

their focus on something less.

I’m actually very well aware that a lot of programming work, nowadays, is not

really rocket science, still this doesn’t mean that it should be done by

completely unqualified people. If what Jeff Atwood says in his post about

programmers who can’t

program is true, and

that is that 199 out of

200 applicants (not

programmers, applicants) can’t write any code whatsoever, than it obviously

means that something is wrong. Looking at the numbers provided by Joel

Spolsky, it looks like a

lot of these basically incompetent people are going to end up working on an

actual programming job, and maybe their code will end up on The Daily

WTF

(Paula,

are you there?).

Unfortunately, the education is not the only one to blame. No matter how much

education will improve, there will always be unqualified people who are

going to apply for jobs that require a lot of skills, and in the end the odds

will help them, so they’ll manage to get a job as a programmer. Is it so bad,

considering that it’s most likely not going to be any critical position, and

the only ones that will be damaged will be the owners of the company that hired

them? Well, the point is that this is not true. There’s someone else who gets

damaged, in this scenario. I’m talking about the community out there, the good

programmers, who find themselves competing with newbies who’re happy to earn

peanuts. The salaries keep going down, and customers are not able to

distinguish a good job from a good one.

In a comment on the previous post of

mine about this

subject, Hoowie Goodell really gets a great

point with this paragraph:

“There has been a great effort to industrialize programming, too. Again,

there are many good features, and it’s a field I’m interested in. Building a

large program requires a structured approach. Language design, libraries,

programming frameworks and IDEs can and should incorporate as much existing

human knowledge as possible: computer science, domain knowledge, solid

pre-written code and human interface principles. (Check out Thomas Greene’s

“Cognitive Dimensions of Notations” for some of the latter: I think of how

programming tools fail to use them on a daily basis!)”

In a way, this suggests that the whole system is not ready yet, as it’s indeed

years and years behind several other engineering fields, and that’s a good

reason, probably, to explain why it’s so easy to fail at being a good

programmer. Let’s just try to get some insightful inspection points, in order

to build better generation of programmers:

-

Better education. The whole higher educational system should be

improved in several way. Worldwide. Nowadays, it looks to me that in many

countries graduation is just a direct consequence of applying to an

University. Unfortunately, this kind of problem must be addressed on a

country-basis, to properly identify the specific issues, but still the

options that I would like to consider are worth mentioning. It all comes

down to a single point: there should be less tolerance towards people

that don’t learn. The thresholds for succeeding in a course should be

raised to greater difficulty. Current models of testing should be

seriously revised, so to ensure that students that really didn’t

understand the subject are not going to make it.

-

Better tools. Are we trying to make programming just like a factory

chain or are we not? If we are, as it seems nowadays, then the tools are

not ready yet to second our intentions. Programming is too error prone

and too time-consuming.

-

Better process. Software process that doesn’t conform to some

standards, say ISO-9000 (sorry if it’s inappropriate, I’m not an expert

on this kind of standards), shouldn’t be allowed to sell. Quality

insurance committees should be taken more seriously as being part of the

process. This might be against all principles of liberalism, I know, as

bad software, you may say, will not sell anyway. I know many bad software

that did sell well, for greatly different reasons than its (non) good quality.

-

Better judgment when hiring. I’m not going to try to teach you how to

run your company, nor how to hire your crew. But sometimes really crazy

thing happen (again, is

Paula

around?). A very interesting post by Joel

Spolsky (I’m sorry, I can’t find it

anymore: does anybody know the link?) talks about only hiring “A”-people,

where “A” means top class. If you’re ever hiring a “B”-person, he’s quite

likely to hire a “C”-person, someday. After that, it’s chaos. I recommend

anyone not to lower their canons of perfections. Here’s another great

article by

Joel,

about hiring good developers, I recommend it.

Concluding, improving the quality of programmers seems really to be a tough

issue, and the whole thing depends on so many factors that tracking a precise

problem is impossible. Cultural and technical difficulties arise all the time,

and getting clues is hard. I’ve tried to get around the problem and give some

insightful opinions: what do you people think?